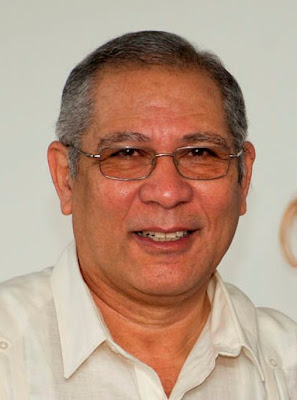

Carlos Alberto Montaner respondiendo a la pregunta: ¿Cuándo comenzará la decadencia norteamericana?

20 de junio de 2015

Estados Unidos ya está en franca decadencia. Por lo menos, esa es la percepción que desea proyectar Russia Today (RT), la voz oficial del Kremlin en Occidente por medio de Internet.

Estados Unidos ya está en franca decadencia. Por lo menos, esa es la percepción que desea proyectar Russia Today (RT), la voz oficial del Kremlin en Occidente por medio de Internet.Más allá de la propaganda, ¿es eso verdad? Al fin y al cabo, todas las potencias hegemónicas algún día dejan de serlo. Francia, que tuvo un siglo XVIII espléndido, o España y Turquía, que reinaron en el XVI y el XVII, son hoy una sombra de lo que fueron.

Se supone que dentro de cinco años el ejército de tierra inglés no será más numeroso que la policía de New York. El Reino Unido, que fue el gran poder planetario en el siglo XIX, se encoge progresivamente, década tras década, y ya ni siquiera es imposible que se desuna y pierda Escocia.

¿Cómo se juzga la fortaleza de una sociedad, incluido el Estado segregado por ella?

A mi juicio, el gran factor que debe tomarse en cuenta es el contorno psicológico de la mayor parte de la gente que la compone. La grandeza o la insignificancia de las sociedades dependen de las percepciones, creencias, valores y actitudes de las personas que la integran.

En Estados Unidos, según las encuestas y la observación más obvia, los individuos respaldan libre y voluntariamente cualquiera de las opciones fundamentales de la democracia liberal (demócratas, republicanos o libertarios).

Las propuestas extremistas o colectivistas a la derecha o la izquierda de este espectro político –y las hay—no alcanzan el menor respaldo popular.

La sociedad, con razón, se queja amargamente del Congreso y sospecha de los políticos, pero no le atribuye las fallas al sistema republicano consagrado en la Constitución de 1787, sino a las personas que lo operan. Esas personas se reemplazan en elecciones periódicas.

Esto le da una enorme fortaleza a las instituciones y genera un altísimo nivel de fiabilidad y confianza. Casi nadie en Estados Unidos teme un futuro abrupto. En el horizonte hay leyes y cambios normados, no revoluciones.

Ese carácter predecible y estable de Estados Unidos ha conseguido que el país se desarrolle al modesto, pero semiconstante ritmo promedio anual del 2%, desde que en 1789 eligieron a George Washington como primer presidente.

Este factor, potenciado por el interés compuesto y por la energía que genera procurar el “sueño americano”, he desatado un crecimiento sostenido al que se han integrado millones de inmigrantes, emprendedores y soñadores de todo tipo.

Ha habido crisis, burbujas y contramarchas, pero la nación fue creciendo desde sus humildes orígenes hasta que a fines del siglo XIX ya era la mayor economía de la Tierra.

Medio siglo más tarde, en 1945, cuando terminó la Segunda Guerra mundial, se había convertido en la primera potencia económica, seguida de cerca por la URSS en el terreno militar.

Si el censo de 1790 arrojó un total de 4 millones de habitantes situados en las 13 excolonias británicas, en el 2015 ya son 320 millones. (En el trayecto –todo hay que decirlo–, mediante compras legítimas, adquisiciones forzadas y despojos, el territorio ha pasado de 2,310,629 kilómetros cuadrados a 9,526,091).

Nada menos que 15 generaciones consecutivas de cuotas crecientes de libertad, trabajo ininterrumpido, acumulación de capital e inversiones protegidas por las leyes, arraigado todo ello en la cosmovisión británica, y en un buen sistema judicial, han dado lugar a un proceso constante de creación de riqueza, aunque a trechos fuera parcialmente obstaculizado por crisis que siempre acababan por superarse.

El dato clave y casi asombroso es éste: la sociedad ha multiplicado su extremadamente heterogénea población por 80, con un mínimo de sobresaltos, salvo la sangrienta Guerra Civil de 1861 a 1865, mientras mejoraban paulatinamente las condiciones de vida para casi todos.

En ese periodo, Estados Unidos no sólo dio un enorme salto demográfico: construyó las mejores universidades del mundo, las fuerzas armadas más poderosas, los centros de investigación científica y técnica más creativos y avanzados, y el tejido empresarial más desarrollado.

¿Hasta cuándo durará esa impetuosa hegemonía? Vuelvo al inicio de estos papeles: mientras las personas crean en el sistema, encuentren espacio para desplegar sus sueños, obtengan incentivos morales y perciban una recompensa material razonable por sus esfuerzos y desvelos, Estados Unidos continuará su marcha triunfal por la historia.

Si en algún momento se descarrila ese proceso y “la gente” deja de valorar positivamente el sistema en el que viven, porque ya no lo encuentran adecuado, y tratan de sustituirlo por otro violentamente, comenzará entonces la decadencia. Los seres humanos no son lo que comen, sino lo que creen.

Published time: September 15, 2010

Edited time: September 15, 2010

Fewer Americans believe in the capitalist system – that’s the result of a new survey. Only slightly more than half of those who were asked, said the free-market economy is what the country needs.

This appears to be a real sign that the nation’s belief in capitalism has been severely shaken by the financial fallout.

Only 53% of American adults believe capitalism is better than socialism. The latest Rasmussen Reports national telephone survey found that 20% disagree and say socialism is better, and 27% are not sure

which is better.

which is better.Adults under 30 are essentially evenly divided: 37% prefer capitalism, 33% socialism, and 30% are undecided. Adults thirty-plus are quite a bit more supportive of the free-enterprise approach with 49% for capitalism and 26% for socialism. Adults over 40 strongly favor capitalism, and just 13% of those older Americans believe socialism is better.

Investors by a 5-to-1 margin choose capitalism. As for those who do not invest, 40% say capitalism is better while 25% prefer socialism.

Rasmussen Reports poll facts

National Survey of 1,000 Adults

Conducted April 6-7, 2009

Margin of Sampling Error, +/- 3 percentage points with a 95% level of confidence

There is a partisan gap as well. Republicans – by an 11-to-1 margin – favor capitalism. Democrats are much more closely divided: Just 39% say capitalism is better, while 30% prefer socialism. As for those not affiliated with either major political party, 48% say capitalism is best, and 21% opt for socialism.

It is interesting to compare the new results to an earlier survey in which 70% of Americans preferred a free-market economy, Rasmussen Reports writes. The fact that a “free-market economy” attracts substantially more support than “capitalism," may suggest some skepticism about whether capitalism in the United States today relies on free markets.

However, the survey did not define the terms ‘capitalism’ and ‘socialism.' But the fact that so many people didn’t answer in favor of capitalism clearly shows that the support for the US economic model is diminishing.

Socialism is understood by most in the country as the increase of government intervention or the redistribution of wealth. Some Republicans in the US have referred to President Barack Obama’s stimulus plan as a down payment on a new American socialist experiment.

*****

Tomado de http://barbwire.com/

Is the American Dream Really Dead?

By Jerry Newcombe

on 31 December, 2014

Last month, a professor of economics at the University of California, Davis made some headlines by basically asserting that there is no American dream. It’s a myth. He crunched the numbers, supposedly disproving it. Hmm. My dad used to always say, “Did you ever hear about the statistician who drowned in a river, the average depth of which was 6 inches?”

KOVR-TV interviewed professor Gregory Clark about his findings. He declared: “America has no higher rate of social mobility than medieval England or pre-industrial Sweden. … That’s the most difficult part about talking about social mobility is because it is shattering people’s dreams.”

Yet America has many “rags to riches” stories. The rest of this article is dedicated to one such case.

Leo Raymond was born in a Faribault, Minnesota, farmhouse Sept. 24, 1921. That town is about an hour south of the Twin Cities. He was one of six children — three boys, three girls. The farmhouse didn’t have electricity when he was growing up, nor did it have indoor plumbing.

Leo had to walk to his one-room schoolhouse, which was a mile away. One of his sons used to quip, “He had to walk uphill, both ways.” But truly, he had to walk to and from school every day, even when it was

really cold. One February, the temperature never got above minus 20.

really cold. One February, the temperature never got above minus 20.Even though that one-room schoolhouse from first to eighth grade was so rudimentary and simple, he got a first-rate education compared with any modern education. His incredible abilities in math and grammar were made secure in that small room.

He was so sharp as a youngster that he skipped second grade, and his mother, a retired schoolteacher, decided to save what paltry money she could to help create a college fund for little Leo. One version of his obituary says that was “a good thing because he hated doing farm chores and couldn’t wait to shake the cow manure off his shoes and see what the big city had to offer.”

Leo became the first in his family to go off to college. He attended the University of Minnesota. This was in 1938, when he was 16. He graduated with a degree in economics in 1942.

He served in the Navy aboard a transport ship in the Pacific, the USS Ulysses S. Grant. After his service in the Navy, he earned an MBA at the University of Michigan in 1947.

Meanwhile, during World War II, he met his wife-to-be, Ann Lombard. She was the daughter of a prominent military surgeon who was transferred a lot during his career.

They got married May 1, 1948, at St. Augustine Cathedral in Pittsburgh. She was born in New Orleans, and her marrying a Yankee was an interesting combination.

It was a wonderful marriage (no civil war there). They settled in the Chicago area, eventually moving to and staying in Winnetka, Illinois. They had eight children — six boys, two girls. They were devout Catholics. They provided everything needed for their children, including quality education at all levels.

Leo became a certified public accountant and worked for Arthur Andersen & Co. He went on to work for Field Enterprises, beginning in 1952. Later, he became the vice president and general manager of the Chicago Sun-Times and Chicago Daily News. He worked for three Marshall Fields — III, IV and V.

This was an amazing achievement — going from a poor farm without an indoor bathroom to becoming an executive for years at two major papers in one of America’s biggest cities.

Tragedy struck Leo in 1977 at the age of 55, in the form of bleeding in the brain. But prayers, organized by his wife, went up all over for him. She oversaw round-the-clock prayer vigils for his recovery, which eventually came. He was never able to drive again, but overall he became his pleasant self again. By God’s grace, his family received the gift of 37 years with him after that.

In 1979, he transitioned from his executive position to teaching accounting at DePaul University. He was tough but well-respected. If you deserved an F, he gave you an F, regardless of your self-esteem. If you deserved an A, you got that, too. He retired in 1991.

Leo was a generous man, always picking up the tab. A whiz at cards, he was “Lucky Leo.”

He was plain-spoken. One time, when he was dining with a high official in the Roman Catholic Church, the cardinal, as I heard the story, had some mayo on his chin. Leo discreetly pointed it out to him. Then the cardinal turned to his underlings and rebuked them for not telling him.

Another time, Leo and a son were in a famous restaurant in New York City. While waiting for a table, he sat next to a man with a strange handlebar mustache at the bar. It was Salvador Dali. Leo had no idea who he was. He said to the artist, “Well, you must have quite a lot of self-esteem to sport a mustache like that. How do you do? I’m Leo.”

Another time, Leo and a son were in a famous restaurant in New York City. While waiting for a table, he sat next to a man with a strange handlebar mustache at the bar. It was Salvador Dali. Leo had no idea who he was. He said to the artist, “Well, you must have quite a lot of self-esteem to sport a mustache like that. How do you do? I’m Leo.”Dali introduced himself, and Leo asked him what he did for a living. Hearing the answer, he told Dali, “A painter? Well, we just settled on a new contract with the painters union, and those guys were tough negotiators.” Dali replied, “Not that kind of painter. I paint on the canvas.” Leo looked surprised and said, “There’s no money in that. How can you afford to eat in a place like Sardi’s?” That’s when Dali roared and insisted on paying for their drinks.

The end of Leo’s earthly time came Dec. 10, 2014, at age 93 at an assisted-care facility in the Chicago area. Not bad for a poor Minnesota farm boy. Long live the American dream.

P.S. I know this is all true because Leo Raymond’s last name was Newcombe. He was my dad.

0 Comments:

Publicar un comentario

<< Home