Reinaldo Taladrid, Vavílov y el “Banco de Semillas del Fin del Mundo”. René Gómez Manzano desde Cuba sobre algunas de las persecuciones comunistas de científicos del pasado

Tomado de https://www.cubanet.org/

Taladrid, Vavílov y el “Banco de Semillas del Fin del Mundo”

*********

Las persecuciones comunistas de científicos del pasado, ¿ofrecen interés o utilidad para el lector de hoy?

*********

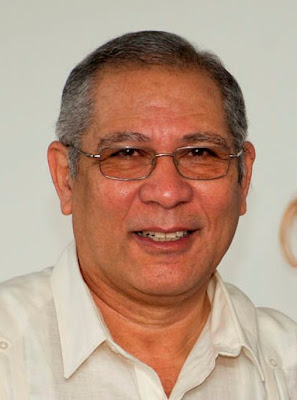

Por René Gómez Manzano

17 de, 2024

LA HABANA, Cuba.- Este domingo 16, el popular e instructivo programa Pasaje a lo desconocido, de la Televisión Cubana, estuvo consagrado a la Cámara Global de Semillas, inaugurada en el año 2008 en el Círculo Polar Ártico, en un monte del archipiélago noruego de Svalbard. Se trata de la misma institución que la prensa, con una truculencia un poco mayor, suele denominar Banco del Fin del Mundo.

LA HABANA, Cuba.- Este domingo 16, el popular e instructivo programa Pasaje a lo desconocido, de la Televisión Cubana, estuvo consagrado a la Cámara Global de Semillas, inaugurada en el año 2008 en el Círculo Polar Ártico, en un monte del archipiélago noruego de Svalbard. Se trata de la misma institución que la prensa, con una truculencia un poco mayor, suele denominar Banco del Fin del Mundo.

La idea que presidió el surgimiento de la institución es simple: que los recursos genéticos botánicos que pudieran perderse como resultado de catástrofes naturales, actos terroristas o conflictos armados puedan ser restablecidos con rapidez y relativa facilidad. Con ese objetivo, la Cámara tiene capacidad para 4,5 millones de muestras, cada una de ellas compuesta por unas 500 semillas, las cuales son conservadas a muy bajas temperaturas.

El mencionado programa televisivo es conducido por Reinaldo Taladrid, un locutor oficialista que suele invitar a sus oyentes a documentarse y concluye sus presentaciones con la frase “Saque usted sus propias conclusiones” (menos cuando se refiere a las políticas del castrocomunismo, claro). El programa de este domingo incluyó la exhibición de varios documentales consagrados al tema antes mencionado.

Es el último de los exhibidos el que me ha animado a escribir este trabajo periodístico. En el material se rememoró al primer científico que aplicó la idea que ahora, con una envergadura mayor, se hace realidad en la Cámara Global de Semillas. Me refiero al ruso Nikolái Ivánovich Vavílov, botánico y genetista que vivió entre 1887 y 1943.

La persecución contra el científico

El referido documental mencionaba la persecución desatada contra el científico por el régimen encabezado por el dictador bolchevique José Stalin. Pero como la obrita fílmica se centraba en la idea de los bancos de semillas —no en las represiones comunistas—, la alusión que se hacía a Vavílov tenía un carácter fugaz e incidental, y puede haber pasado inadvertida para muchos de los espectadores.

Me parece que, para beneficio de los amigos lectores de CubaNet, sería harto conveniente que se abunde un poco más en este importante tema. Esto, a su vez, permitirá conocer mejor el carácter monstruoso de las persecuciones comunistas, sus motivaciones arbitrarias y espurias, las cuales, entre otras cosas, han producido enormes perjuicios a la misma causa que dicen defender los burócratas y policías que las han perpetrado.

Es lo mismo que, en otro orden de cosas, sucedió con la cibernética. A Stalin, que se las daba de filósofo, le dio por considerar que esa rama, consagrada a obtener, conservar y transmitir información, era “anti-marxista”, ya que negaba la esencia del pensamiento humano como forma superior de la materia… Se comprende, entonces, que en el Diccionario Filosófico de 1954, por ejemplo, se la caracterizara como una “seudociencia reaccionaria… dirigida contra la dialéctica materialista”. Este despiste teórico, a su vez, condujo a un retraso de lustros con respecto a la ciencia de los países occidentales.

La labor de Vavílov

Volviendo a Vavílov y a la genética, debo adelantar que su destino fue aún más trágico que el de los estudiosos consagrados a la cibernética. El eminente botánico partió de una idea sencilla, pero certera: durante milenios, los agricultores han seleccionado las variedades de vegetales; en ello los ha guiado el propósito fundamental de obtener mayores cantidades y un producto de mejor sabor.

Por ello se hacía necesario buscar, en las zonas originarias de las diferentes especies comerciales, los parientes silvestres que pudiesen conservar genes que permitieran a las plantas soportar mejor las condiciones adversas (plagas, cambios bruscos de clima, etc.). Con ese fin, Nikolái Ivánovich encabezó innumerables expediciones científicas. Con las muestras obtenidas en ellas, creó el primer banco de semillas del mundo; el material genético que obtuvo de las variedades silvestres recolectadas fue enorme.

Vavílov se basaba en las teorías de otro genio de la ciencia: el austriaco Gregor Mendel, descubridor de las leyes de la herencia. Para desgracia del botánico ruso, el concepto mismo de que las plantas pudiesen heredar y transmitir genes les parecía antimarxista y “burgués” a Stalin y su claque. Además, el dictador georgiano no tenía paciencia para asimilar los planes a largo plazo que diseñaba Vavílov para garantizar la seguridad alimentaria global.

Vavílov regulado por Stalin

Es ahí cuando entra en escena Trofim Lysenko. Se trataba de un verdadero charlatán. Rechazaba como “reaccionarias” las enseñanzas de Mendel y, en lo referente a la evolución de las especies, se atenía a los planteamientos de Jean-Baptist Lamarck. Este último fue un científico cuyas teorías fueron emitidas varios decenios antes de Darwin, y resultaron superadas por este. Pese a ello, a Lysenko se le concedieron los mayores honores; en 1948 se decidió que el lysenkoísmo debería enseñarse como la única teoría correcta en ese campo. Esa situación se mantuvo hasta mediados de los años sesenta.

En el ínterin, la persecución estalinista se cebó en Vavílov. Se le prohibió volver a viajar al extranjero (en la neolengua castrista de hoy se diría que fue “regulado”). También perdió los altos cargos que ostentaba. En definitiva, en el debate científico intervino la policía política.

En agosto de 1940 fue arrestado bajo acusaciones de “espionaje” y “sabotaje”. Sentenciado a muerte en julio del año siguiente, la pena (generosos que son estos comunistas) le fue conmutada por 20 años de prisión.

A partir de ahí, Nikolái Ivánovich conoció las islas del tenebroso “Archipiélago GULAG”. En el colmo de la ironía, el gran científico que consagró todos sus desvelos a librar a la Humanidad del flagelo terrible de las hambrunas, murió a comienzos de 1943, en una cárcel de Sarátov,… ¡de inanición!

************

Algunas incidencias del totalitarismo comunista en las Matemáticas: Los casos Égorov y Luzín.

Egorov held spiritual beliefs to be of great importance, and openly defended the Church against Marxist supporters after the Russian Revolution. He was elected president of the Moscow Mathematical Society in 1921, and became director of the Institute for Mechanics and Mathematics at Moscow State University in 1923. However because of Egorov's stance against the repression of the Church, he was dismissed from the Institute in 1929 and publicly rebuked. In 1930 he was arrested and imprisoned as a "religious sectarian", and soon after was expelled from the Moscow Mathematical Society.

Egorov held spiritual beliefs to be of great importance, and openly defended the Church against Marxist supporters after the Russian Revolution. He was elected president of the Moscow Mathematical Society in 1921, and became director of the Institute for Mechanics and Mathematics at Moscow State University in 1923. However because of Egorov's stance against the repression of the Church, he was dismissed from the Institute in 1929 and publicly rebuked. In 1930 he was arrested and imprisoned as a "religious sectarian", and soon after was expelled from the Moscow Mathematical Society.(Dmitri_Egorov)

Upon imprisonment, Egorov began a hunger strike until he was taken to the prison hospital, and eventually to the house of fellow mathematician Nikolai Chebotaryov where he died.

*******

(fragmento)

Hubo en la vida de A. Kolmogorov y algunos otros matemáticos de su generación un episodio desagradable conocido como el "Proceso de Luzin" (ver [14]). En 1936 la elite partidista inició una acció n contra el viejo fundador de la escuela matemática moscovita, donde se formaron, entre otros, los brillantes A. Khinchine, P. Alexandrov, A. Kolmogorov.

Hubo en la vida de A. Kolmogorov y algunos otros matemáticos de su generación un episodio desagradable conocido como el "Proceso de Luzin" (ver [14]). En 1936 la elite partidista inició una acció n contra el viejo fundador de la escuela matemática moscovita, donde se formaron, entre otros, los brillantes A. Khinchine, P. Alexandrov, A. Kolmogorov.(Nikolai N. Luzin)

Este ¨proceso", que afortunadamente no llegó hasta sus ultimas consecuencias, fue emprendido en 1936 por razones puramente políticas. En vísperas de la guerra con Alemania, los mejores matemáticos sovi eticos publicaban en el extranjero, en especial, en Alemania. A pesar de que se trataba de una práctica común, este argumento fue utilizado contra N.N. Luzin, para mostrar su falta de patriotismo. Con el fin de inculpar a Luzin, todavía fuera de tribunales, se organizó una comisión especial de la Academia de Ciencias de la URSS. Se atrajeron en calidad de "acusadores potenciales" a colegas y alumnos de Luzin. Y si bien algunos matemáticos conocidos de la generación mayor (S. Bernstien, A. Krylov, I. Vinogradov) se pronunciaron en su defensa justamente opinando que los "errores" reales y ficticios de N. Luzin no correspondían ni a la décima parte de las acusaciones que le imputaban, muchos de sus jóvenes alumnos (A. Khinchine, P. Alexandrov, A. Kolmogorov entre otros) y colegas (B. Sigal, S. Sobolev) que apoyaron las acusaciones. Es notable que el acusador más agresivo fuera el conocido topólogo P. S. Alexandrov (amigo cercano de Kolmogorov) quien ya en aquel entonces [2] tenía serios conflictos con Luzin. La postura tan hostil y agresiva de una parte de la comunidad matemática soviética, que llegó hasta acusarlo de causar daño a la URSS y casi de espiar a favor de Alemania, hubiera podido llevar a que Luzin, ya de avanzada edad y destruido moralmente, compartiera el destino de su maestro, el famoso matemático D. Egorov que falleció en el

campo de concentración. Afortunadamente, como creen los autores de la investigación [2], Stalin consideró que la \lecci on de patriotismo" ya hab a sido impartida y dio ordenes de

campo de concentración. Afortunadamente, como creen los autores de la investigación [2], Stalin consideró que la \lecci on de patriotismo" ya hab a sido impartida y dio ordenes de(Andrey N. Kolmogorov)

Tomado de https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pavel_Alexandrov

This article incorporates information from the Russian Wikipedia.

Pavel Alexandrov should not be confused with Aleksandr Danilovich Aleksandrov, another mathematician at the Steklov Institute.

Born May 7, 1896

Bogorodsk, Moscow Governorate, Russian Empire

Died November 16, 1982 (aged 86)

Moscow, Soviet Union

Nationality Soviet Union

Fields Mathematics

Alma mater Moscow State University

Doctoral advisor Dmitri Egorov

Nikolai Luzin

Doctoral students Aleksandr Kurosh

Lev Pontryagin

Andrey Tychonoff

Honours and awards of Pavel Sergeyevich Alexandrov

Hero of Socialist Labour

Stalin Prize

Order of Lenin, six times (1946, 1953, 1961, 1966, 1969 and 1975)

Order of the October Revolution

Order of the Red Banner of Labour

Order of the Badge of Honour

************

The Luzin affair of 1936

On 21 November 1930 the declaration of the “initiative group” of the Moscow Mathematical Society which consisted of former Luzin's students Lazar Lyusternik and Lev Shnirelman along with Alexander Gelfond and Lev Pontryagin claimed that “there appeared active counter-revolutionaries among mathematicians.” Some of these mathematicians were pointed out, including the advisor of Luzin, Dmitri Egorov. In September 1930, Dmitri Egorov was arrested on the basis of his religious beliefs. After arrest, he left the position of the director of the Moscow Mathematical Society. The new director became Ernst Kolman. As a result, Luzin left the Moscow Mathematical Society and Moscow State University. Egorov died on 10 September 1931, after a hunger strike initiated in prison. In 1931, Ernst Kolman made the first complaint against Luzin.

In July–August 1936, Luzin was criticised in Pravda in a series of anonymous articles whose authorship later was attributed to Ernst Kolman.[6] The attack on Luzin was supported by some of his students and was instigated by a letter of Pavel Aleksandroff.[7] It was alleged that Luzin published “would-be scientific papers,” “felt no shame in declaring the discoveries of his students to be his own achievements,” stood close to the ideology of the “black hundreds,” orthodoxy, and monarchy “fascist-type modernized but slightly.” Luzin was tried at a special hearing of the Commission of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, which endorsed all accusations of Luzin as an enemy under the mask of a Soviet citizen. One of the complaints was that he published his major results in foreign journals. Aleksandroff, Kolmogorov and some other students of Luzin accused him in plagiarism and various forms of misconduct.[8] Sergei Sobolev and Otto Schmidt incriminated disloyalty to Soviet power. The methods of political insinuations and slander were used against the old Muscovite professorship many years before the article in Pravda. Although the Commission convicted Luzin, he was neither expelled from the Academy nor arrested, but his department in the Steklov Institute was closed and he lost all his official positions . There has been some speculation about why his punishment was so much milder than that of most other people condemned at that time, but the reason for this does not seem to be known for certain. Historian of mathematics A.P. Yushkevich speculated that at the time, Stalin was more concerned with the forthcoming Moscow Trials of Lev Kamenev, Grigory Zinoviev and others, whereas the eventual fate of Luzin was of a little interest to him.[9] The 1936 decision of the Academy of Sciences was not cancelled after Stalin's death.[10][11] The decision was finally reversed on January 17, 2012.[12][13]

Tomado de http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Extras/Luzin.html

The 1936 Luzin affair

Delo akademika Nikolaya Nikolaevicha Luzina. (Russian)

[The case of Academician Nikolai Nikolaevich Luzin]

Edited by S. S. Demidov and B.V. Levshin. Russkii Khristianskii Gumanitarnyi Institut, St Petersburg, 1999. 312 pp.

Reviewed by F. Smithies

This book gives a full account of the "Luzin affair" of 1936, when an attempt was made to discredit the Russian mathematician Nikolai Luzin and have him expelled from the Academy of Sciences.

Details of the affair became available from about 1990 onwards, and an investigation, originally led by the late A. P. Yushkevich, was set on foot; its results are described in the present volume. The main descriptive text is by S. S. Demidov and V. D. Esakov, but is described as having been accomplished "with the collective help of the scientific community".

The authors describe the background of Moscow mathematics from 1920 onwards; an important school, in real-variable theory, was led by Luzin, and was nicknamed ("Luzitania"). They remark that Stalin's repression was weaker in mathematics than in some other sciences. The chief sufferer was D. T. Egorov, who had led an important school before World War I; he was attacked as a reactionary, was arrested in 1930, and died in exile in 1931. The Moscow Mathematical Society saved its skin by censuring Egorov and electing Ernest Kolman as president; Kolman was a loyal Bolshevik and an active ideologue, who became head of the scientific section of the Moscow party committee, but he was not generally taken seriously as a mathematician.

The Egorov affair alarmed Luzin, who had only recently returned from a long trip abroad; he gave up his university work, took refuge in the Central Aero-Hydrodynamics Institute in Leningrad, and worked in the Steklov Institute there. He continued to be head of the mathematical group in the Academy of Sciences.

Kolman attacked Luzin in print, associating him with Egorov and other reactionaries, and alleged that he was tainted with Fascism; this denunciation prevented Luzin from going to the international congress at Zurich in 1932. Very much later an OGPU file was discovered alleging that Luzin had met Hitler and received instructions from him.

The Academy and the Steklov Institute were both moved from Leningrad to Moscow in 1934, with the intention of giving the Academy a leading role in the development of Soviet science, making it a world leader, under the control of the Party and the Government.

The attack on Luzin began after he was asked to report on some school tests, and reported in an invited article in Izvestiya on 27 June 1936 that he found the standard surprisingly high. An article in Pravda on 2 July accused him of hypocritical praise, with the aim of smearing over inefficiencies and harming the school. An anonymous article on 3 July, almost certainly by Kolman, accused Luzin of

(i) praising weak work,

(ii) publishing his best papers in the West, and only second-rate ones in the USSR,

(iii) claiming his pupils' results as his own (in particular, those of Suslin and Novikov),

(iv) keeping good young candidates out of the Academy, and

(v) continuing to hold reactionary ideas from Tsarist times. It also described Luzin as "an enemy in a Soviet mask". Mekhlis, the editor of Pravda, immediately wrote to the Party's Central Committee, which authorised further inquiries, especially on item (ii).

On the same day a meeting of members of the Steklov Institute passed a vote of censure on Luzin, and asked the Presidium of the Academy to examine Luzin's position as head of the commission on the qualifications of prospective members.

Over the next few days, the Presidium decided to set up a special commission to investigate the accusations in the Pravda article, under the chairmanship of Krzhizhanovskii, who had been made vice-president in 1929, and had been given the task of overseeing the work of the Academy from the Party's point of view; he had direct access to Stalin.

A meeting of Moscow mathematicians on 7 July passed an anti-Luzin resolution. A stenographic record of the meetings of the special commission has survived. The commission met on alternate days from 7 to 13 July; the record of its meetings is reprinted in the present volume, and has been briefly annotated.

The tone of the first three meetings (7, 9 and 11 July) grew more and more aggressive towards Luzin; he was attacked by S. L. Sobolev, Shnirelman and Khinchin and defended by S. N. Bernstein. P. S. Aleksandrov agreed that Luzin had taken over Suslin's work, but kept his criticisms on an ethical level, with no hint of political wrong-doing. On the third day Sobolev raised the question of Luzin's exclusion from the Academy. On the same day Luzin attended the meeting by invitation; he defended himself for publishing his theoretical work abroad, on the grounds that it had no immediate practical value; he also attacked Kolman's mathematical competence. The wording of a draft resolution was discussed; in later drafts the words about harming the Soviet Union were omitted, as were those about subservience to the West, which had been the theme of a Pravda article on 9 July.

At the next sitting (13 July) the tone of the meeting had completely changed. It appears that Krzhizhanovskii had had a word with Stalin, who had asked for more factual specifics about some of the accusations, and asked for any resolution to be phrased in academic language; the upshot was that the softer form of the resolution was accepted, one that did not echo the more abusive remarks of the Pravda articles, such as the phrase about "an enemy in a Soviet mask". Luzin made a statement, promising to take account of the criticisms, and to publish primarily in the Soviet Union; his statement was received with understanding and sympathy. The authors indulge in a good deal of speculation about the reasons behind this remarkable reversal.

At the sitting on 15 July, the tone was sympathetic to Luzin, who was defended by several members. Krzhizhanovskii, as chairman, adhered closely to the formal resolution; he summarised the conclusion as saying that Luzin's behaviour was not on the level that should be expected from an Academician, and that he had been given a warning.

There is some evidence that another meeting may have taken place on 19 July; if so, no record of it has survived. The final text of the resolution reached the party's Central Committee by 25 July. Pravda continued its anti-Luzin campaign in articles on 15 July and on 6 August, but they provoked little notice. Eventually Gelfond and Shnirelman published a destructive review of Kolman's book on methods in mathematics, and he lost his position on the Moscow committee of the Party.

Publication of mathematical papers abroad had hitherto been common, but now practically ceased.

Luzin himself lost his university post and his role in selecting new members of the Academy, but remained an Academician. A certain alienation developed between some of the older academicians such as Bernstein, Vinogradov, A. N. Krylov and Luzin himself and some of the up-and-coming young men such as Aleksandrov, Sobolev and A. Ya. Khinchin. Nevertheless, the Soviet mathematical community recovered remarkably rapidly from the Luzin affair.

A number of documents are reprinted at the end of the book, including the Pravda articles, the resolutions passed at various meetings, and a selection of letters.

Reviewed by F. Smithies

Copyright © American Mathematical Society 2001, 2004

Etiquetas: Banco de Semillas del Fin del Mundo, biología, científica, científicos, comunismo. genética, cuba, Lysenko, matemáticas, Mendel. teorías, persecusión, semillas, Stalin, Unión Soviética, URSS, Vavílov

0 Comments:

Publicar un comentario

<< Home