Caroline Overington: Land of rum and rumba blighted by communism

http://www.theaustralian.news.com.au/story/0,20867,20251894-7583,00.html

Caroline Overington: Land of rum and rumba blighted by communism

By Caroline Overington

August 26, 2006

TWO years ago, I was given what quickly became an awful assignment. I was told to visit Cuba. Oh sure, like everybody I thought: dark rum, hot nights, fat cigars, the rumba.

TWO years ago, I was given what quickly became an awful assignment. I was told to visit Cuba. Oh sure, like everybody I thought: dark rum, hot nights, fat cigars, the rumba.The reality was very different. Cuba was wretched. Every day the photographer and I encountered distressing scenes of women, children and ageing Cubans living in terrible poverty.

Walking down the streets of Old Havana, we saw a very old, wrinkled woman sitting in the gutter. She was wearing a skirt with multicoloured petticoats. She had bright red lipstick and her two front teeth were missing. She was smiling a crooked smile and sucking on a long Cuban cigar.

The old woman - a grandmother, probably - was sitting there not because she was a happy little communist, as Fidel Castro would have it, not because she was thrilled with his socialist revolution, but because she was dirt-poor and hungry.

Aged 70 or older, she was in a gutter begging, hoping that a Western tourist such as me would come by, see her pretty dress and her gap-toothed smile, and exclaim: "Oh, look at you! May we take your photo?" Of course she would agree, and stick out a bony hand for an American dollar.

Elsewhere, we found barefoot children searching through rubbish bins for food. There is a large black population in Cuba - many of them are descendants of sugar-cane cutters - and there were many blacks among the beggars. Women with babies at the breast tugged at our clothes, begging for pennies.

In the Western-style bars, beautiful Cuban girls hung off the arms of Western men.

We drove into the countryside and found people living with open sewers and dirt floors, with no food, no coffee, no rum, no pork, no music, none of the things a Cuban needs to thrive.

Castro's revolution - free food, free education, free health care for all - was a sad, sorry joke. The classrooms were decrepit, the school books so old as to be useless. Store shelves were empty.

It was a police state, too. Nobody would speak ill of Castro (if they did, it was quietly, with a pale, strained face and a furtive glance over the shoulder).

We visited the homes of dissidents and heard that librarians, poets and free-marketeers - good, friendly people - had been taken to prison, some of them sentenced to 20 years or more in a cell no larger than a toilet block, forced to walk around and around in circles, 400km from home in a nation where it's impossible to visit anybody unless you hitch a ride in the back of a creaking, humpbacked truck known as a "camel", made in eastern Europe and liable to break down in the Cuban heat.

It was a terrible shock because, like many people, I'd believed the hype about Cuba: that it was a socialist paradise; that Castro was a visionary leader; that the Cuban people were happy communists. In fact, Castro is a gutless dictator who has never been brave enough to hold a presidential election. Yet across the West he continues to be celebrated as some grand, visionary leader, instead of being derided as a lunatic on his last legs.

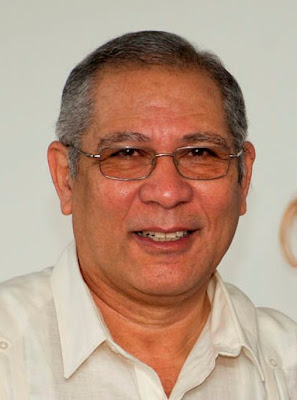

Now there is a new book, Child of the Revolution, by Cuban-Australian Luis M. Garcia, who was born in the small Cuban village of Banes in 1959, just six months after Castro - the wealthy son of Spanish-born landowners - launched the revolution.

Garcia's book is not political. It's romantic, passionate and tremendously amusing. But he doesn't ignore the creeping horror of Castro's regime.

His parents' shop - a modest enterprise - was taken from them. Food quickly became scarce (except disgusting Hungarian meat in pressed jelly, fish heads and pigs' trotters, which were plentiful).

Cuban women, who had previously enjoyed hot nights with their families, dancing the rumba, drinking sweet coffee and partaking of prayer, took to trudging around the streets carrying la jaba - a cheap old shopping bag - in search of food. Not everybody was poor, of course: go to the website therealcuba.com and you can see aerial shots of Castro's large residences, as well as gruesome pictures of old Cuban men facing the firing squad.

When Garcia's father - poor, beaten, hungry - finally made the wrenching decision to leave Cuba, he was sent to a labour camp and forced to cut sugar cane for three years for no pay, surviving on a diet of liquid stew made of peas.

When Garcia's father - poor, beaten, hungry - finally made the wrenching decision to leave Cuba, he was sent to a labour camp and forced to cut sugar cane for three years for no pay, surviving on a diet of liquid stew made of peas.The young Luis, meanwhile, went to a camp for boy communists. When his mother wanted to visit, she had to swap her dress and a pair of shoes for some beans and pork fat so she could make him a stew.

When she couldn't hitch a ride on a humpbacked jeep, she walked through the Cuban heat for four hours, with her heavy jaba stuffed with food. to make sure her boy was all right.

Garcia captures the exquisite pain of leaving Cuba, too. Like all families, his was told: when you go, that's it, you are considered a traitor and you can never come back. You will never see a Cuban sunset, a Cuban beach, again.

Garcia has lived in Australia with his grateful parents since 1972. He's married now, with children. He published his book in June. In July came news that Castro was ill and in August he handed over power to his younger brother, Raul, at least temporarily.

The Cuban community is alive with gossip that Castro - now 80 - is nearing the end of his life and his reign. In Miami, where so many exiled Cubans live, there's a nonstop party under way.

Garcia says he's not sure how he feels about the fact that Castro will soon be dead. "I am apprehensive," he says. "Who knows what might happen next? But then I think: whatever happens, it can't be worse."

He's being polite, but I don't have to be. When I hear that Castro might soon be dead, well, it makes me want to flip up my skirt and dance a Cuban rumba.

overingtonc@theaustralian.com.au

0 Comments:

Publicar un comentario

<< Home